Sometimes good intentions backfire. That’s what happened with Boston’s Age Strong Campaign. Organized by Boston’s Aging Commission with support from the Mayor, the campaign aims to dispel stereotypes about old people and promote positive messaging about aging. Unfortunately, it risks doing just the opposite.

For starters, although the word “strong” is a heartfelt choice for Boston, Boston Age Strong reinforces the notion that optimal function, attractiveness, and independence determine a human being’s worthiness for attention and compassion. That’s dangerous territory, and not just for elders.

The campaign’s message makes good sense at first glance. Age Strong highlights eight stereotypic labels for old people – frumpy, cranky, inactive, senile, frail, childish, over the hill, and helpless – and features elders to whom those labels do not apply. Although more elders have none of these attributes than many, they are not without foundation. A campaign that identified the root causes for each label’s association with old age would do more good than one that shows they aren’t always true.

Certain old age stereotypes, including frumpy and cranky, sometimes apply to elders for reasons that have less to do with aging than with our social and cultural responses to old people. For example, an old person may appear “frumpy” because she is unable to find clothing that looks good and fits her body. Human bodies shrink and shift with age, waists shorten, and different anatomic parts seem most worthy of being featured. Yet in fashion as in countless other sectors, our biases set up a self-perpetuating cycle: assuming old people don’t care about appearance, manufacturers make plain, functional clothing for them; unable to find anything else that fits, old people are forced to don drab, shapeless clothes, thereby reinforcing the public perception that fashion doesn’t concern them.

Definitions from SF Reframing Aging

The crankiness label raises different issues. A person might be cranky because everyone he loved best has died or because society provides him neither place nor purpose and his consequent isolation and loneliness are only occasionally relieved by a family visit or medical appointment. And an elder might be cranky because their doctor, with little or no training about older bodies and lives, has written off their pain and debility to “old age” even though age is not a diagnosis but a risk factor.

Crankiness is not an unreasonable response to living in a world where you are overlooked or ignored in blatant, unrecognized ways. Take public parks. Designed to promote play, exercise, and social engagement, most offer cute, colorful playgrounds for children and basketball courts, baseball and soccer fields for adults. Few provide elderhood equivalents, such as pickleball, tai chi, and level walking paths. People without opportunities for exercise and social interaction are more likely to be cranky.

Of course, a person also might be cranky in old age – or childish, or anything else – because they always were.

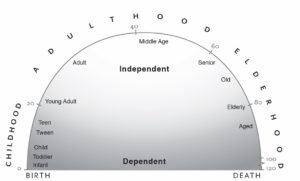

And for a middle aged or old person to say they are not over the hill is just plain silly. Assuming the metaphorical hill of life is relatively symmetric, then most of us are over it sometime between the ages of thirty-six and forty-two. The problem isn’t the label’s accuracy, it’s that it’s too often used as an insult rather than a statement of fact.

The Commission’s website declares that it “works toward making Boston a city that fully embraces aging.” But the campaign elevates the earlier substages of elderhood at the expense of the later ones. Barring premature death, we will all become less active and frail, a sizeable minority of us will develop dementia, and we will all need help. That isn’t failure – it’s successful aging. A frail old person is one who has survived the entire arc of the human lifecycle.

Admittedly, too many people are assumed to be frail or ‘senile’ simply because they are old. But an ableist, shortsighted campaign won’t change that. To quote the legendary writer, Ursula K. LeGuin, “If you don’t see my age, you don’t see me.”

None of the traps Boston’s Age Strong campaign fell into are new. That smart, dedicated people miscalculated should be seen primarily as evidence that elderhood, like childhood and adulthood, can’t be accurately captured by a single word or message. As we geriatricians like to say, “If you’ve seen one eighty-year-old, you’ve seen one eighty-year-old.”