Recently, a pediatrician friend remarked that people – patients’ parents, friends, strangers she chats with briefly in airports and coffee lines – were always asking her for recommendations on the best books about childhood.

I had to admit that I don’t get many requests about books on old age.

That’s a shame, because there are a lot of them, and some are quite good. But in looking through my growing collection of these books to decide which I might recommend if I were ever asked, I realized that there isn’t a single ‘books about aging’ genre.

It turns out that books about aging tend to be one of five types:

(There are more of each than I could possibly list, so I’ve listed the first two examples of each that popped into my mind, since otherwise I’d never finish this blog post…)

1. Informational or “how to”. These are books people read when they need them, but neither one nanosecond before that nor one nanosecond after. They are the workhorses: useful but not necessarily entertaining or endowed with greater meaning or existential value.

- The 36-hour Day: A Family Guide to Caring for Persons with Alzheimer Disease, by Nancy Mace and Peter V. Rabins

- Eldercare for Dummies, by Rachelle Zukerman

2. Memoirs, usually about the author’s experience caring for her aging parents. In these books, facts and advice, even diatribes, often punctuate the narrative. All are born of grief and celebration, anguish and guilt and confusion. Many are moving, some are stunning, few do as well as one might expect in the marketplace, though it’s unclear whether this status is a consequence of the subject matter itself or the genre, a blur of memoir, lament and advice.

- A Bittersweet Season, by Jane Gross

- Knocking on Heaven’s Door, by Katy Butler

3. Wellness and longevity books. These range from tips on healthy aging to shameless manipulation of people’s greatest fears and perpetuation of their dearest delusions. (Too) many suggest that if a person eats enough blueberries and kale and has the right attitude (as described in the author’s books) they will not have to age or die. Little or no mention is made of bad luck, bad genes, poverty, racism, and other uncontrollable factors and social injustices. Sometimes this is true even when the author’s name is followed by those telltale initials: M and D.

- In the spirit of ‘if you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all’, I offer no examples

- You will know these books when you see them

4. General non-fiction. These are sometimes written by experts and sometimes by journalists who did extensive research. They include facts and anecdotes making them both readable and informative. They often focus on one aspect of aging, such as dementia or nursing homes.

- Old Friends, by Tracy Kidder

- The Forgetting, by David Shenk

5. Literary works. These can be fiction or non-fiction but hold true to the rules of literature: beautiful sentences, fully realized characters, and good stories that explore universal themes.

- Memento Mori, Muriel Spark

- The Lemon Table, Julian Barnes

Of course, for every listing of this sort there are exceptions or rule benders. Two of my recent favorites fall in this category:

RUNNER-UP: Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? By Roz Chast. This is a memoir by the famed New Yorker cartoonist that is funny, sad, apt, compelling, personal, universal and one-of-a-kind.

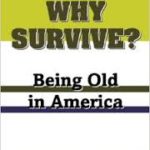

WINNER: This book wasn’t published this year, or last year, or even this decade or last decade. It came out in the 1970s before I read such books. Why Survive? Being Old in America, by Robert Butler. It was written by a physician*, and it won the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction. Equally notable, though I haven’t finished it yet, most of the facts, challenges and attitudes described are as true today as they were all those decades ago. Which is another reason to read the book: we need to do better, and soon!

Next time: Great blogs on aging

* Butler makes the rest of us look like slouches: In addition to winning the Pulitzer, he founded the National Institutes on Aging and the first department of geriatrics at an American medical school, and he helped found the Alzheimer’s Disease Association, the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry, the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Alliance for Aging Research.